Protecting investments in Latin America – Navigating political risk with Bilateral Investment Treaties

1. Introduction

The Latin American region (LatAm) presents appealing investment opportunities for international investors. With a population of 656 million inhabitants (read potential market), a wealth of natural resources and a market that includes the 9th and the 12th largest economies in the world (i.e., Brazil and Mexico, respectively) the region is attractive from a business perspective.

However, investing in LatAm countries implies considerable political risks which must be dealt with. These political risks include (extreme) left governments, (semi-)dictatorship environments and a great deal of political and economic instability.

Under this environment, asset protection has become an important driver when structuring investments into LatAm. Specifically, entitlement to Bilateral Investment Treaty protection (BIT) is currently an important element sought by international investors.

We discuss below some relevant aspects of Luxembourg BITs as well as some comments from recent practical experience structuring investments into the LatAm region.

2. Overview of BITs

BITs are international agreements between two countries that contain reciprocal undertakings for the promotion and protection of private investments. There are currently approximately 2,222 BITs in force along with some 390 multilateral investment treaties and trade agreements with investment provisions.

Currently, Luxembourg (more specifically, the Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union (BLEU)) has the following BITs in force with LatAm countries:

- Argentina

- Chile

- El Salvador

- Guatemala

- Mexico

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

The following BITs have been signed but are not yet in force:

- Brazil

- Colombia

- Costa Rica

- Cuba

- Nicaragua

- Panama

3. Some relevant concepts

Under a BIT, a foreign investor has the right to initiate an arbitration procedure against the host state, where an investment is located, for violation of the substantive protections set forth in the relevant BIT.

The substantive protections include (among others):

- Prohibition on unreasonable or discriminatory measures,

- Compensation for an unlawful expropriation (including indirect expropriation),

- Fair and equitable treatment,

- Full protection and security,

- National treatment,

- Most-favoured-nation treatment,

- Free transfer of payments, and

- Umbrella clauses (i.e., guarantee of any commitments the state has entered into in relation to investments).

“Under a BIT, a foreign investor has the right to initiate an arbitration procedure against the host state, where an investment is located, for violation of the substantive protections set forth in the relevant BIT.”

In practice, the substantive protection most frequently sought by international investors investing in LatAm is compensation for unlawful expropriation and fair and equitable treatment. We have seen in particular an increasing interest in using these protections against confiscatory tax measures implemented by states – see further below.

What is an investment?

The term “investment” is defined broadly in most BITs to include “every kind of asset” with a non-exclusive list of examples, including:

- movable and immovable property,

- mortgages, liens, pledges and usufructs,

- shares, parts or any other form of participation in companies,

- claims to money or to any performance having an economic value,

- copyrights, industrial property rights, technical processes, know-how and goodwill, and

- concessions under public law.

It is noted in this respect that the protection under many BITs extends to both “direct” and “indirect” investments.

Who is an investor?

Under a BIT, investors can be natural persons or legal persons.

In the case of natural persons, investors are the nationals of a contracting state but note that there may be limitations on dual nationals. For example, an individual holding Luxembourg and Mexican nationalities who invests in Mexico may not have access to the BIT between the BLEU and Mexico.

In the case of legal entities, there are varying definitions. Some BITs only require:

- incorporation in the contracting state;

- others require (1) incorporation and (2) a seat of business (siège reel or siège social) or a registered office in the contracting state;

- others require (1) incorporation, (2) a seat of business/registered office, and (3) “real” or “substantial” economic activities in the contracting state.

Example:

An international investor acquiring, through a Luxembourg holding company, the Mexican holding company of an industrial group including different Mexican companies and manufacturing facilities located in Mexico would in principle have access to the protection of the BLEU – Mexico BIT.

In this case, the Luxembourg holding company would qualify as an ‘investor’; the ‘investments’ would include the Mexican holding company and the companies underneath as well as the manufacturing facilities (as indirect investments). We note in this respect that the BLEU – Mexico BIT is of the type discussed in point ii above, i.e., arguably, the Luxembourg holding company would not need to have real or substantial economic activities in Luxembourg (its holding activity would suffice).

“In practice, the substantive protection most frequently sought by international investors investing in LatAm is compensation for unlawful expropriation and fair and equitable treatment.”

The concept of ‘confiscatory taxation’

An increasing number of claims are being brought in relation to confiscatory tax measures implemented by states. These claims are typically brought under the (indirect) expropriation and fair-and-equitable-treatment provisions in BITs (and occur most commonly, but not exclusively, in the oil-and-gas and mining sectors).

Investors have challenged a variety of tax-related measures, including corporate income tax, VAT or sales tax, and import/export taxes (including withdrawal of tax benefits/subsidies).

In view of the increasing number of claims, some states are introducing tax-related carve-outs in more recent treaties (over 40 percent of BITs entered into since 2010 include such carve-outs).

Who administers arbitration procedures?

The arbitration procedures may be submitted to arbitration administered:

- By the International Centre for Settlement Disputes (ICSID) or

- Under the arbitration rules of the UN Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) or

- By another international arbitral institution (less commonly).

We note in this respect that awards issued under the framework of ICSID, an organization that is part of the World Bank, tend to be followed by states precisely because it is an entity that is part of the World Bank.

Are BITs actually used?

The dispute-resolution provisions in BITs are frequently invoked by investors, and there has been a significant increase in the use of arbitration under BITs in recent years. Recent examples of awards include the following:

- In 2024, Argentina was ordered to pay USD 160 million to a Kuwaiti company in relation to a contract to provide customs inspection services.

- Peru has reportedly been ordered to pay damages to a Spanish-led consortium in the first of a trio of ICSID claims over a project to build a new metro line in Lima.

- Clorox won a USD 109 million award arising from price control measures enacted by the Venezuelan government that forced Clorox to close its production facilities in Venezuela in 2014.

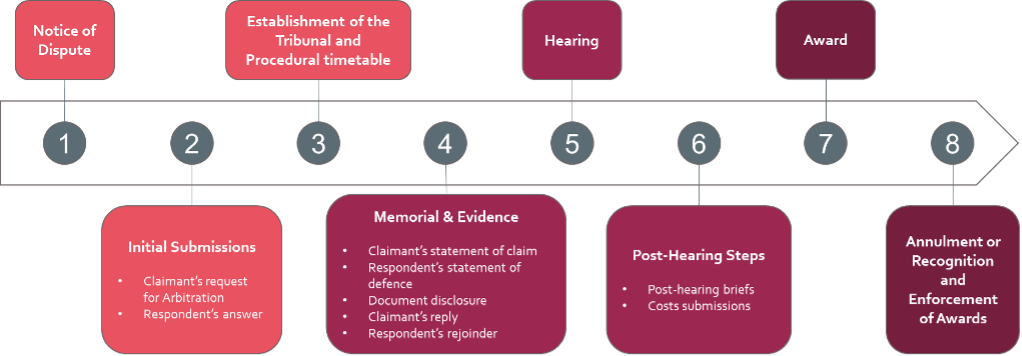

4. The typical Procedural Steps in an Investment Treaty Arbitration

Some time and costs estimations

- On average, investment treaty arbitration cases can take about 4.5 years.

- The average costs incurred in an investment treaty arbitration by claimants are approximately USD 6.4 million.

- The average costs incurred in an investment treaty arbitration by respondents (states) are approximately USD 4.7 million.

- Among successful claims, the average amount of damages sought is USD 1.5 billion

Authors

David Cordova Flores

Tax Partner

Charles Russell Speechlys SCS

Thomas Snider

Partner, Head of International Arbitration

Charles Russell Speechlys SCS

Search posts by topic

Advisory (7)

Alternative Investment (24)

Alternative investments (3)

AML (1)

Art (1)

Asset Management (27)

Banking (16)

Capital Markets (1)

Compliance (1)

Crypto-assets (3)

Digital Assets (3)

Digital banking (6)

Diversity (7)

EU (6)

Family Businesses (4)

Family Offices (2)

Fintech (10)

Fund distribution (22)

Governance (8)

HR (9)

ICT (1)

Independent Director (5)

Insurance (2)

Internationalization (1)

LATAM (9)

Legal (10)

Private Equity (4)

Regulation (1)

Reinsurance (2)

RRHH (9)

Sustainable Finance (23)

Tax (15)

Technology (6)

Transfer Pricing (2)

Trends (18)

Unit-linked life insurance (6)

Wealth Management (12)